The Battle of the Little Bighorn, also known as Custer’s Last Stand, was the most ferocious battle of the Sioux Wars. Colonel George Custer and his men never stood a fighting chance.

Under skies darkened by smoke, gunfire, and flying arrows, 210 men of the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry, led by Lt. Colonel George Custer, confronted thousands of Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne warriors on June 25, 1876, near the Little Bighorn River in present-day Montana. This clash was part of the ongoing battles and negotiations over control of Western territory, collectively known as the Sioux Wars.

In less than an hour, the Sioux and Cheyenne had won the battle, killing Custer and all his men. Though it has been called “Custer’s Last Stand,” Custer and his men never had a fighting chance.

Custer’s Early Life and Career

George Armstrong Custer, born in Ohio in 1839, earned a teaching certificate in 1856 but had grander goals. He entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1857, where he graduated last in his class in 1861.

During the Civil War, Custer joined the Union Army’s Cavalry and proved himself a competent soldier in battles like the First Battle of Bull Run and Gettysburg. By the war’s end, he was a Major General in charge of a Cavalry division.

Custer was known for his resilience, leading from the front and often being the first to plunge into battle. In 1866, he was promoted to Lt. Colonel and commanded the 7th U.S. Cavalry, fighting in the Plains Indian Wars.

The Plains Indians’ Struggle

The Great Plains were the last stronghold for Native Americans. As settlers moved west, conflicts over land became inevitable. By the late 1860s, many Native Americans were forced onto reservations or killed. The Plains tribes, determined to avoid this fate, fought fiercely to defend their land.

The U.S. government, seeking to weaken the tribes, allowed the railroads to kill buffalo herds. This infuriated the Indigenous people, who relied on buffalo for survival. By the time Custer arrived in 1866, the war between the army and the Plains tribes was intense.

Custer’s Court-Martial and Return

Custer’s first assignment was a shock-and-awe campaign against the tribes. After deserting to join his wife, he was court-martialed and suspended in 1867. Despite this, the army needed him, and he returned to command in 1868, leading a ruthless campaign against a Cheyenne village led by Chief Black Kettle.

Encounter with Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse

In 1873, Custer faced Lakota warriors led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse at Yellowstone. This was his first encounter with the leaders who would later play a role in his death.

In 1868, the U.S. government recognized South Dakota’s Black Hills as part of the Great Sioux Reservation. However, the discovery of gold in 1874 led the government to break the treaty. Custer was tasked with relocating all Native Americans in the area by January 31, 1876.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn

The U.S. Army dispatched three columns of soldiers, including Custer’s 7th Cavalry, to round up the tribes and return them to reservations. Custer, ignoring the plan to wait for reinforcements, launched a surprise attack on June 25, 1876.

Custer divided his 600 men into four groups. Major Marcus Reno’s group attacked first but retreated in disarray. Captain Frederick Benteen’s troops joined Reno, but neither moved to assist Custer despite hearing heavy gunfire from his position.

Custer and his men faced overwhelming numbers of Sioux and Cheyenne warriors armed with superior weaponry. In the end, Custer and all 210 men of his battalion were killed.

Aftermath and Legacy

The Native Americans celebrated their victory, but it was short-lived. The U.S. Army intensified its efforts, eventually forcing most tribes onto reservations.

In May 1877, Crazy Horse surrendered and was later killed. Sitting Bull surrendered in 1881 and lived on the Standing Rock Reservation until his death in 1890.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn remains controversial. Custer is often accused of arrogance for leading his men to their deaths, while others blame Reno and Benteen for not aiding him. Regardless, the battle is one of the most recognized events in U.S. history, immortalized by Libbie Custer’s efforts to portray her husband as a hero.

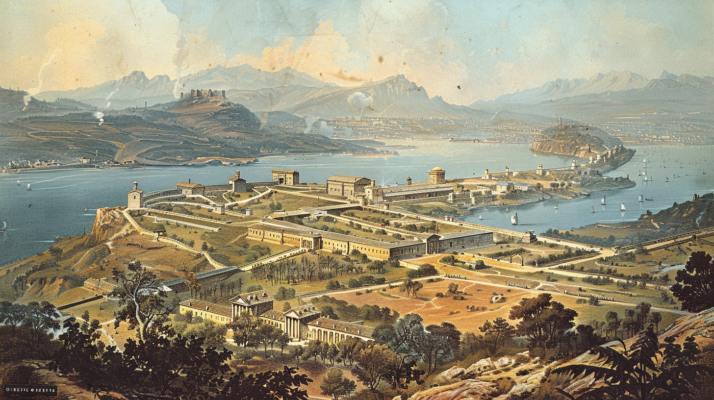

The battle’s dead were quickly buried where they fell. Custer was later reburied at West Point, and a memorial was erected in 1881. Despite the controversy, the Battle of the Little Bighorn endures as a pivotal moment in American history.